In a forthcoming essay, I argue that Thoreau’s Walden can be read as an example of “Condition-of-(New) England” literature. The “Condition of England” describes a genre of writing closely associated with Industrial England of the 1830s, 40s, and 50s. I use the term Condition of (New) England to describe a larger transatlantic dialogue over the social conditions of industrialization that took place at the same time. My essay will appear in an edited collection that emerges from a conference on “Thoreau and the Nick of Time” that I participated in 2022 in Reykholt, Iceland. Due to considerations of space, I could not include the following section in my final draft, so I’m posting it separately here.

Thoreau’s commentary on the overworked laborer forms part of a larger discussion of work, freedom, and slavery which is the occasion for some Thoreau’s most famous—as well as some of his most problematic—reflections. These reflections can be understood more clearly, however, when they are read in the context of the Condition-of-(New) England discourse from which they emerged.

“I sometimes wonder that we can be so frivolous, I may almost say, as to attend to the gross but somewhat foreign form of servitude called Negro Slavery, there are so many keen and subtle masters that enslave both north and south,” Thoreau writes. “It is hard to have a southern overseer; it is worse to have a northern one; but worst of all when you are the slave-driver of yourself.”

The problematic aspects of this passage should be obvious to 21st-century readers: the idea that it would be “frivolous” to care about the enslavement of African Americans is only slightly less offensive than the suggestion that being a “slave-driver of yourself”—a metaphor—is harder than being literally bound in chains and forced to work under penalty of severe corporal punishment or death. What was Thoreau—a staunch abolitionist who defended John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry—trying to say with such words?

To begin with, it is worth noting that the penchant for condemning abuses taking place far away while ignoring those closer to home was a favorite target of Condition-of-England writers, epitomized by Charles Dickens’s term “telescopic philanthropy,” coined in his 1853 novel Bleak House. That owners of cotton mills who employed child labor could also be ardent abolitionists was fodder for social reformers who charged such people with hypocrisy. (Echoes of such rhetoric can be heard in Thoreau’s takedown of philanthropy in Walden.) Carlyle joined in the chorus of such criticisms in Past and Present when he favorably compared the situation of the feudal thrall “Gurth, with the brass collar around his neck” to “many a Lancashire and Buckinghamshire man of these days, not born thrall of anybody!” Whereas the former was at least clothed, fed, and housed, the latter was wholly at the mercy of the market. “Liberty, I am told, is a divine thing,” Carlyle wrote. “Liberty when it becomes the ‘Liberty to die by starvation’ is not so divine!”—lines quoted by the American social reformer and founding member of the Republican Party Alvan Bovay in a speech that was reprinted in the New England working-class and Chartist press.1

Orestes Brownson had argued similarly in “The Laboring Classes,” expressing his condemnation of slavery in all forms while arguing that the wage laborer was actually worse off than the enslaved person because the wage worker’s situation was more precarious: “the laborer at wages has all the disadvantages of freedom and none of its blessings, while the slave, if denied the blessings, is freed from the disadvantages.” (He surely underestimated the disadvantages of being enslaved.)

The idea—however problematically expressed—was that freedom in the absence of property or a social guarantee of subsistence was purely formal. It offered the wage worker nothing by way of material security and thus left them little room to make genuine choices when it came to selling their time and capacity to work in the labor market. Such arguments belonged to what political theorists call “labor republicanism,” a tradition of political thought in which liberty is defined in terms of freedom from domination and dependence. In this tradition, workers’ dependence on, and subjection to, their employers make them unfree.

One of the most sophisticated expositions of this line of argument was put forth by Charles Dana in the pages of the Harbinger, the journal of the utopian socialist Brook Farm community, of which Dana was a member. Brook Farm was founded in 1840 by George Ripley, one of the leading early Transcendentalists. While the community began as an experiment in implementing Transcendentalist principles, it later embraced the “associationist” ideas of the utopian socialist Charles Fourier, officially becoming a “Phalanx” in 1844.2 Born in Buffalo, New York, Dana was a reformer, journalist, and “public intellectual” who later served as an undersecretary of war in Abraham Lincoln’s administration during the Civil War. Like Thoreau, he attended Harvard and was attracted to Transcendentalist ideas.3 At Brook Farm, he was personally close with Ripley, acting as his “right-hand man.”4

In his article, which was a critical review of three recent discussions of the factories at Lowell, Dana condemned the long hours of work in the Lowell mills—drawing comparisons with the situation of workers in England—and contested the notion that such labor was performed “voluntarily” by the women who undertook it. Workers were driven to the mills by economic circumstances, Dana argued, which he called “the Whip of Necessity.” “Is anyone such a fool as to suppose that out of six thousand factory girls of Lowell, sixty would be there if they could help it?” he asked:

Every body knows that it is necessity alone … that takes them to Lowell and that keeps them there. Is this freedom? To our minds it is slavery quite as real as any in Turkey or Carolina. It matters little as to the fact of slavery, whether the slave be compelled to his tasks by the whip of the overseer or the wages of the Lowell Corporation. In either case it is not his own free will, leading him to work, but an outward necessity that puts free will out of the question.

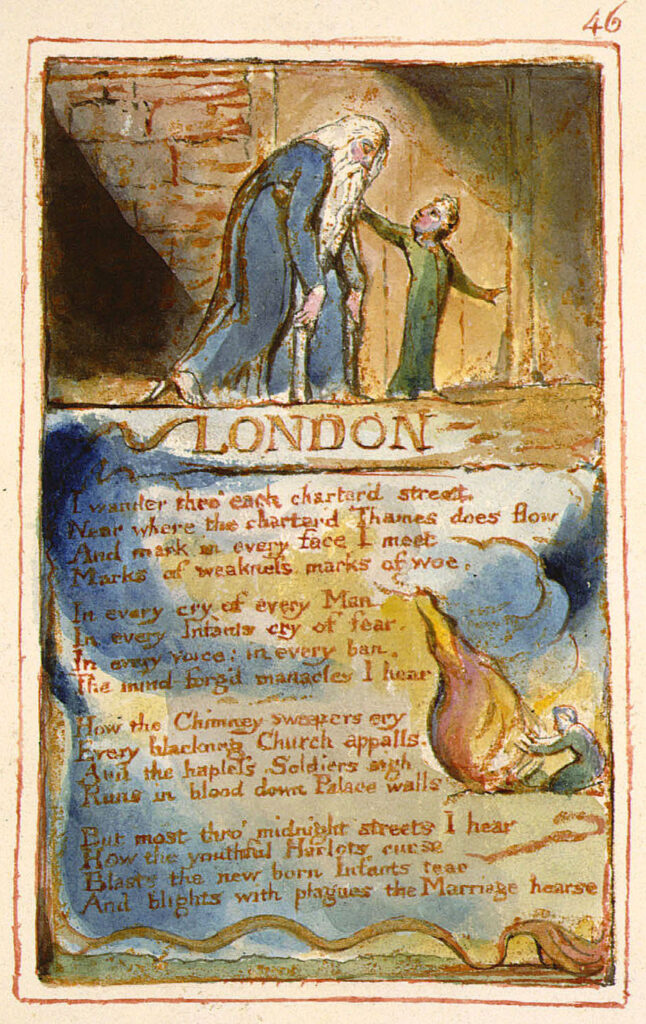

This, then is the tradition out of which Thoreau’s comments on slavery emerge. For Thoreau, however, the subjection to the industrial social order went even deeper in that it emanated from people’s own ideas about themselves, prejudices which kept them imprisoned within narrow confines of their own making and which required a revolution in consciousness to undo. This idea bears an affinity with what the poet William Blake called, in a slightly different context, “mind-forg’d manacles.” It is also not unrelated to Marx’s idea that modern society is defined by the “mute” or “silent compulsion of economic relations,” a notion echoed in Thoreau’s other famous aphorism—which follows closely on his comment about slavery—that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” According to Thoreau, not even “games and amusement” are safe from such pervasive despair: “There is no play in them, for this comes after work.”

Read in social and historical context, this cluster of ideas and metaphors—mind forg’d manacles, self-enslavement, silent compulsion, quiet desperation—suggests an attempt to grasp the new realities of industrial capitalism—not only new experiences of industrial work, defined by its long hours, but new forms of power in which control is exercised economically rather than politically, implicitly rather than explicitly. The impersonal domination of the clock supersedes the personal domination of the master. Partly at issue is the force which Dana identifies: the worker is driven by the “whip of necessity,” a social force that acquires an impersonal, deceptively natural, form. Whereas for Dana and others sympathetic to socialism, the “slavery of wages” implied the need for collective action—whether through labor unions, planned communities, or legislative reform—for Thoreau, it had to be primarily resisted by the individual. By freeing themselves from false definitions of success which equate it with the endless acquisition of “superfluous” material possessions, a person can reclaim their time, which for Thoreau is their true source of wealth.

- Voice of Industry, July 31, 1845. For more on Bovay and the National Reform Association that he helped to lead, see Mark Lause, Young America: Land, Labor, and the Republican Community, University of Illinois Press, 2005. ↩︎

- On Brook Farm and the relation between Transcendentalism and Fourierism, see Richard Francis, “The Ideology of Brook Farm,” Studies in the American Renaissance (ed. Joel Myerson, 1977), pp 1-48. ↩︎

- Eric X. Rivas, “Charles A. Dana, the Civil War Era, and American Republicanism” (doctoral dissertation), 48. ↩︎

- “Ideology of Brook Farm,” 5 ↩︎